The Discovering Literature: Shakespeare has just launched.

Shakespeare portrait sale has major U of G connection

Shakespeare portrait sale has major U of G connection

Note that this is article dates from December 16, 2013 and is here being captured to the CASP website pursuant on the Guelph Mercury having ceased to publish.

Guelph Mercury

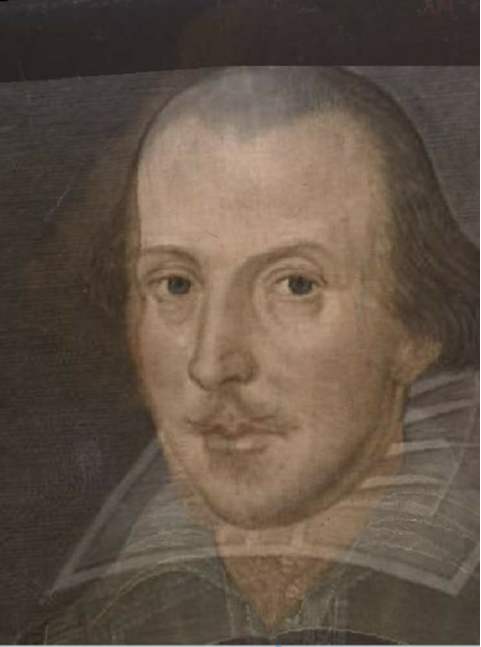

GUELPH – After a massive investigation involving many layers of scientific analysis, intricate genealogical mapping, and stacks of scholarly evidence, a University of Guelph researcher has concluded that the so-called Sanders portrait is as close to a genuine likeness of William Shakespeare there is.

“I’m convinced that of all the images out there, it absolutely has the most evidence and is the most credible painting,” said Daniel Fischlin, a professor in the school of English and theatre studies, and head of U of G’s Canada Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. “There is not a single other image out there that is even close to this level of evidence.”

He, along with U of G president Alastair Summerlee, have long championed the authenticity of the portrait, owned by Canadian Lloyd Sullivan, and supported research into its origins. Both appeared to play pivotal roles in the recent sale of the painting, which was reported Monday by the Globe and Mail.

“It’s the first portrait of Shakespeare to sell,” Fischlin said. “It’s really the first image of Shakespeare, with this level of evidence, to sell, and it’s happening here in Canada. It’s incredible.”

For the past several months, Fischlin has engaged in tireless research, including making a trip to England to firm up evidence that the portrait is the real thing. Lloyd Sullivan’s lineage has been traced back to John Sanders, a great grandfather 13 generations removed, who was among Shakespeare’s “most intimate associates,” Fischlin said.

Fischlin became friends with Sullivan some years ago and agreed to find hard evidence that the portrait dates back to Shakespeare’s time. Sullivan, now in his 80s, is frail, and has been working for several years, and spent close to a $1 million, trying to authenticate it and find a home for it in a public institution.

The Globe and Mail reported Monday that a buyer has been found for the portrait, and that an unspecified, but significant, amount of money is being paid for it. The portrait was painted in 1603, 13 years before Shakespeare’s death. The Globe reported that Summerlee was instrumental in finding a buyer for it.

“It’s a big story, with many years of work coming together,” said Fischlin in an interview Monday. He would only state its value as “zero to priceless.” He confirmed that there is a buyer, but said he was not privy to the selling price.

“It’s been a big push over the last four or five months,” said Fischlin, a tone of exhaustion in his voice. “Part of it was the situation for the owner of the portrait, who is elderly, and it would not have been good for either him or this portrait should he have died in this process.”

A number of tax implications and legacy issues swarmed around the portrait. Given Sullivan’s effort to safeguard and authenticate the portrait, it would only be right for him to benefit from the sale, while achieving the aim of finding it a permanent, public home, Fischlin indicated.

“It became really apparent to us in the last six months or so that we really had to make push come to shove, and bring out the evidence in a coherent space that brought together the experts who have done their due diligence,” Fischlin said.

The Globe and Mail reported that there has been mounting evidence that the portrait is the only existing likeness of Shakespeare done during the playwright’s lifetime. The university recently hosted a symposium in Toronto on the painting in which genealogy, costumery, provenance, history and forensics experts attested to its authenticity, the Globe reported.

The symposium, Fischlin said, was an opportunity to bring all the principals together to publicly disclose all of the evidence.

Some years ago, Fischlin asked the portrait’s owner if he could use an image of it as the splash page of his website. Since then, the scholar has been invested in the life, investigation and fate of the portrait.

“In August, I went over to England for a bunch of weeks to do due diligence, and this was part of Alastair Summerlee wanting me to have a hard look at the evidence,” Fischlin said.

He added that while in Britain he travelled to virtually every spot the Sanders family had lived and uncovered a great deal of new evidence related to the family

Sullivan, who has owned the portrait for 40 years, told the Globe and Mail that the sale of the portrait has not yet been finalized, and expressed anxiety about the portrait leaving the country if the sale doesn’t go through. But, he indicated he was happy to be nearing a conclusion after years of investigation into the portrait’s authenticity.

December 16, 2013

roflanagan@guelphmercury.com

Shakespeare yet lives, in Guelph at that

Shakespeare yet lives, in Guelph at that

“Shakespeare is a drunken savage with some imagination whose plays please only in London and Canada.”

Impressive: In one line, Voltaire managed to offend both the playwright considered by many to be the greatest writer in the English language and also the country now thought by more than a few to be the best place on Earth.

At least the Canadians were in good company.

This spring marks four centuries since Shakespeare’s death on April 23.

Today Voltaire might be surprised to learn that the Bard’s work still attracts readers and theatre-goers — although the news that many of those enthusiasts live in Canada might only confirm his opinions of both the colonies and the Elizabethan playwright.

If anything, Shakespeare is even more popular in Canada now than he was in Voltaire’s day, with numerous adaptations of his work every year.

Some of those happen at the Stratford Festival, of course. But many more play out in other places across the country.

Capturing the spirit of those and other productions is the point of the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project (CASP) run by Daniel Fischlin, an English professor at the University of Guelph.

Launched in 2003, the site now includes more than 700 adaptations since Confederation.

Among the earliest was “Shakspere’s Skull and Falstaff’s Nose: A Fancy in Three Acts.” It was published pseudonymously in 1889 in London by Charles Moyse, a McGill University English professor.

That was only the beginning of many Shakespeare spoofs, including “Tryst and Snout,” a musical hillbilly adaptation of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” by Guelph’s James Gordon.

Other productions contain more serious subtexts. “Hamlet-le-Malecite” was produced in 2004 by Ondinnok, the only First Nations theatre company in Quebec. With its messages about colonization and indigenous peoples, this adaptation might have resonated with Voltaire at least.

Fischlin says Quebec tends to produce provocative adaptations of Shakespeare, often linked to proto-nationalist ideas. There, as elsewhere, more pop-cultural references show up in recent adaptations, along with discussion of issues from sexual identity to race and class.

That trend might offend Shakespearean purists. But Fischlin figures many viewers might come to Shakespeare through adaptations.

That includes movies ranging from “The Lion King” (hard not to hear echoes of “Hamlet” in the “evil uncle” trope of Scar) to “West Side Story” (a New York City retelling of “Romeo and Juliet”).

“Anything that brings people into contact with creativity is a good thing,” says Fischlin, who grew up in Montreal reading his dad’s collected works of Shakespeare.

In Guelph, he’s now busy updating the CASP website with dozens of new adaptations staged in Canada since 2005.

Among other things, the site also contains links to clips of Canadian performances, including plays, movies, TV shows, documentaries and cartoons — and plenty of other Shakespeare Canadiana. In a cheeky move, Fischlin has borrowed Voltaire’s “drunken savage” quotation as a tag line for the website.

Canadian ties run through yet another project involving Fischlin and CASP.

He has been involved in an effort to authenticate the so-called Sanders portrait, purported to be the only likeness of the Bard painted in his lifetime.

The portrait, long owned by retired Ottawa engineer Lloyd Sullivan, is believed to have descended through 13 generations of his family.

Numerous scientific tests of the painting, including the paint itself and the frame as well as an inscription on the back of the portrait, all point to the conclusion that we are indeed looking at the Bard.

It’s a pile of circumstantial evidence, a pile heightened further by genealogical research connecting Shakespeare’s family with that of Sullivan. Sullivan family lore says the portraitist was John Sanders, a family ancestor and a member of Shakespeare’s acting company.

This month, new information appeared on the CASP site, including information about a newspaper article believed to be the earliest known public reference to the portrait.

Fischlin has travelled back and forth to England himself, including a visit in 2013 when he took in London — imagine Voltaire’s shudder — to look into connections there between Shakespeare, John Sanders and other associates of the day.

After James I succeeded Elizabeth I on the throne, Shakespeare ran the King’s Men as an early entertainment business. Fischlin figures Canada would have fed that entrepreneurial spirit.

“He would look at Canada as an opportunity for more of the same.”

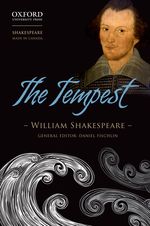

Fischlin is also producing a new edition of several of Shakespeare’s works, published initially by Oxford University Press and now by Rock’s Mills Press.

Four hundred years after his death, the Bard lives on in Canada. Who — including Voltaire — could have imagined?

Andrew Vowles is a Guelph writer

Three Key Documents Related to the Genealogical Research on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare

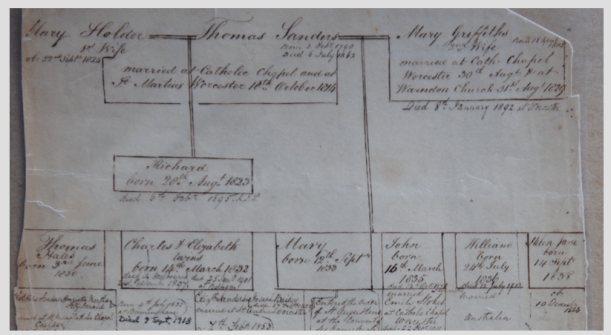

CASP is pleased to publish three key documents related to the genealogical research that has taken many years of work both in Canada and in the UK: 1) Thomas Hales Sanders’ last will and testament, which set the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare on course to its present owner, Lloyd Sullivan (his great-grandson); 2) the Sanders Family Bible, whose pages laid out crucial information about the family genealogy that served as a guide for Pam Hinks’s extensive genealogical work in the Midlands; 3) the earliest known public reference to the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare dating back to October 1862.

These documents were, effectively, the place at which the extended research on the portrait began. They are published by CASP for the first time together in the same place along with a short note by James Hales-Sanders (also a great grandson of Thomas Hales Sanders) about the sequence of events that make this Family Bible such an important part of the overall story.

• The Sanders Family Bible

Lloyd Sullivan’s mother, Kathleen, passed the Sanders painting to her only son just before she died in 1972 with the proviso that it would make a great retirement project, someday.

Lloyd Sullivan placed the painting on his dining room wall where it constantly reminded him of his mother’s wish that he undertake authentication of the family treasure, well-known throughout the family of aunts, uncles and cousins, and generally within family lore, as being a portrait of the great William Shakespeare, putatively painted by an ancestor during the Bard’s lifetime.

Retired from Bell Canada management in 1991 Lloyd Sullivan made the decision to begin the authentication process. He had no experience in the art world and very little genealogical experience. Fortunately, at the same time his mother handed him the painting, she also entrusted the family Bible to his care, a large and heavy book acquired by our great-grandfather, Thomas Hale-Sanders.

As was the custom in the early 1800s, family history was recorded in the Bible, which was published in a Second Edition in December 1816 in Liverpool by Nuttall Fisher & Dixon, who were located on Duke Street and known for their good quality family Bibles. The Bible is large, full-calf bound in generally good order (despite foxing and binding degradation), with an attractive leather bookplate, marbled end-papers, and beautiful copper plate engravings throughout.

Like other Bibles from the same publisher and from the same period, it includes separate entries with a list of births and deaths of the Sanders family over several generations. Originally published in 1609 (just six years after the Sanders portrait was painted), the Old Testament portion of the Bible was the work of the English College at Douay, and the New Testament version used in the Bible was first published by the English College at Rheims in 1582.

Publication Information (Sanders Family Bible)

The information contained on the first pages of the family Bible provided Lloyd Sullivan with the all-important genealogical starting point to discovering his early ancestral origins, an arduous and time-consuming research project that ultimately led back to a startling array of family connections between Lloyd’s direct ancestors and Shakespeare’s inner circle.

Sanders Family Bible (detail of genealogical entries)

Like the Bible itself, Lloyd Sullivan’s journey would be long and laborious and similar to the Bible, he would discover that both the painting and the Good Book had survived floods, fires, and wars.

There are many other sources discovered over many years of research, but this Bible was the original starting point for the genealogical research on the Sanders Portrait of William Shakespeare.

James Hale-Sanders (January 2016)

• Thomas Hale-Sanders’ Last Will and Testament (Proved December 14, 1915)

Note that the will explicitly mentions the family Bible and gives it to Thomas Hale-Sanders’ son, Aloysius, along with the “reputed portrait of Shakespeare dated 1603.” Thomas Hale-Sanders’ will is careful to underline the “reputed” nature of the portrait, the full dimensions of the research required across multiple disciplines (scientific, genealogical, and internal and contextual evidence) largely unavailable to researchers at this point in time in the early twentieth century.

Below are photos of Thomas Hale-Sanders’ house in Worcester taken in 2013 by Daniel Fischlin as part of a research trip into the Midlands–the last known place in England where the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare resided before it was brought to Canada after Thomas’s death.

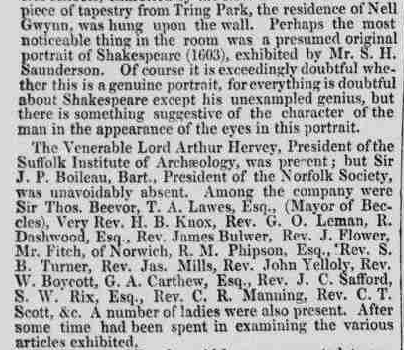

• Earliest Known Public Reference to the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare

Finally, CASP is pleased to publish here the earliest known public reference to the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare, dated October 4, 1862 from The Ipswich Journal. We include in the gallery the full journal from that date, with the specific reference to the Sanders portrait found on page 8 of the journal proper (“Suffolk and Norfolk Institutes of Archaeology Meeting at Eccles”).

The Ipswich Journal October 4, 1862

The Journal reports that: “In the room was a presumed original portrait of Shakespeare. It had been in the family of the gentleman who exhibited it for nearly a century, and had always been considered to be an original portrait of Shakespeare.”

And …

“Perhaps the most noticeable thing in the room was a presumed original portrait of Shakespeare (1603), exhibited by Mr. S. H. Saunderson [sic; and presumably T.H. Sanders, Thomas Hale-Sanders, Lloyd Sullivan’s great-grandfather]. Of course, it is exceedingly doubtful whether this is a genuine portrait, for everything is doubtful about Shakespeare except his unexampled genius, but there is something suggestive of the character of the man in the appearance of the eyes in this portrait.”

Sanders Portrait mention in Ipswich Journal (detail)

Thomas Hale-Sanders’ (THS) father was Thomas Sanders who was christened Feb, 16, 1790 and died July 6, 1862. This exhibition took place in October 1862, so shortly after Thomas Hales Sanders inherited the portrait from his father. THS may well have been trying to promote the recently inherited portrait, possibly with some hope of selling it. The name of the owner is given in The Ipswich Journal report as S. H. Saunderson, which would not be the first (or last) instance of a reporter misreporting a name.

The description of the portrait, especially the mention of the eyes and the fact that it is dated 1603, is wholly consistent with the Sanders portrait and the report uses similar language to the M.H.A. Spielmann essay, written almost half a century later.

Victorian art critic M.H.A Spielmann (1858-1948); as painted by John Henry Frederick Bacon

That essay states: “It had been in the family of the gentleman who exhibited it for nearly a century, and had always been considered to be an original portrait of Shakespeare.” Spielmann quotes Thomas Hale-Sanders as saying “that the portrait had been for nearly a century in the possession of his relations, and had always been supposed to be a portrait of Shakespeare.”

The Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: Game-changing Research

In November 2015 the Council of Ontario Universities named the work done on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare as being in the top 50 game-changing research undertakings in Ontario over the last 100 years. Click here for the University of Guelph announcement and here for the Council of Ontario Universities general site announcement.

2014

A research team led by Daniel Fischlin at the University of Guelph confirmed that a 400-year-old painting is very likely the only genuine image of William Shakespeare created while the Elizabethan playwright was alive. Named for the Sanders family, its owners over some thirteen generations, “The Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare” is the only Shakespearean historical artifact that gives his birth date (April 23), coincidentally the same day on which he died. The Sander’s descendants immigrated with the portrait to Canada in the early part of the twentieth century, which is how Fischlin and his researchers eventually got involved.

Using scientific, historical, and genealogical evidence, researchers have demonstrated that the portrait depicts the Bard in 1603 at age 39, a critical moment in Shakespeare’s history after he had completed the writing of Hamlet and been made a King’s Man. The portrait remains a much researched, much debated document related to one of history’s most influential writers.

See also:

University of Guelph discoveries in running to be named biggest research ‘game changers’

Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: A Partial Bibliography

In the interests of showing the extent to which the Sanders Portrait has garnered international attention as the scholarship on it has deepened, CASP is pleased to publish the following partial bibliography, which dates the earliest known public mention of the portrait to 1862 and then continues on through the early twentieth century through to the present.

Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare Bibliography (partial*)

Books, Scholarly Articles, & Symposium Presentations

Adams, James, Anne Henderson, and Robert Enright. “Reception History and Media: The Portrait as Story Machine.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

Bretz, Andrew. “The Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: Genealogy and Provenance.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

______.”Family Friend: Tracing the Provenance of the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare.” WLU English and Film Studies Research in Progress Talks. Waterloo, ON. 15 November 2013.

______. “’Shall I draw the curtain?’: Shakespeare Portraits and the ‘Air’ of Genius.” Renaissance Society of America. Berlin, Germany. 26-28 March 2015.

Burnett, Mark Thornton, Adrian Streete, Ramona Wray. The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011.

Corbeil, Marie-Claude. “The Scientific Examination of the Sanders Portrait of William Shakespeare.” Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI). Ottawa: CCI, 2008.

______. “The Scientific Evidence: Reading the Wood, Paint, Paper, Glue.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

DeWitt, Lloyd. “The Sanders Portrait as a Painting: an Art Historical Perspective.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

Fedderson, Kim and Michael J. Richardson. “Shakespeare’s Multiple Metamorphoses: Authenticity Agonistes.” College Literature 36:1 (2009): 1-19.

Fischlin, Daniel. ed. Outerspeares: Shakespeare, Intermedia, and the Limits of Adaptation. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

______. ed. “Look Here Upon this Picture:” Unveiling the Mystery of the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto: University of Toronto Press (in progress).

Fischlin, Daniel and Judith Nasby. Shakespeare––Made in Canada: Contemporary Canadian Adaptations in Theatre, Pop Media and Visual Arts. Guelph, ON: Macdonald Stewart Arts Centre, 2007.

Hearn, Karen. “Are you there, Will? The myths about the supposed portraits of Shakespeare are put to rest in London, but the sitter remains as elusive as ever.” Apollo (2006) 163.531: 80.

Kahan, Jeffrey. “Is the Sanders Portrait Genuine?” Shakespeare Newsletter (2001-2002) 51.4: 81-102.

Makaryk, Irene. Shakespeare in Canada: A World Elsewhere. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Minard, Kathryn, David Loch, Jane Freeman. “What’s the Value of Priceless? Hard Dollars vs. Legacy Issues.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

Nolan, Stephanie. Shakespeare’s Face. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Priest, Dale G. “Sexual Shakespeare: Forgery, Authorship, Portraiture (Review).” The Sixteenth Century Journal (2002) 33.3: 924-925.

Salter, Denis W. “Staging Canada.” Theater (2004) 34:3. 146-152.

Searching for Shakespeare. Ed. Tarnya Cooper. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006.

Smith, Bruce. “THWS, CWWS, WSAF, and WSCI in the Shakespeare book biz. (The Historical William Shakespeare, Collected Works William Shakespeare, William Shakespeare as Author Function, William Shakespeare as Cultural Icon.” Shakespeare Studies (2007) 35: 158-186.

Spielmann, Marion Henry. “The ‘Grafton’ and ‘Sanders’ Portraits of Shakespeare.” The Connoisseur. XXIII (February 1909): 97-102.

Sullivan, Lloyd. “This Is the Face of the Bard.” In Fischlin, Daniel and Judith Nasby. Shakespeare––Made in Canada: Contemporary Canadian Adaptations in Theatre, Pop Media and Visual Arts. Guelph, ON: Macdonald Stewart Arts Centre, 2007. 25-42.

Thackray, Anne. “Shakespeare? Exhibiting ‘The Sanders Portrait’ at the Art Gallery of Ontario.” The British Art Journal. (2002) 3:2: 72-76.

Tiramani, Jenny. “The Sanders Portrait.” Costume. (2005) 39:1: 44-52.

______. “The Sanders Portrait: An examination of Internal Evidence and Sumptuary Law.” Look Here Upon This Picture: A Symposium on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. Toronto, ON. 28 November 2013.

Newspapers & Periodicals

“Portrait of Shakespeare?” Montreal Gazette 18 July 1964: 12.

“Relics of Theatre on Exhibition Today… 1603 Portrait of Shakespeare is of Chief Interest.” The New York Times. 18 October 1928.

“TO SELL PORTRAIT OF SHAKESPEARE; Direct Descendant of Sanders …” The New York Times 19 October 1928.

Bloom, Harold. “Picturing Shakespeare”. Vanity Fair. December 2001: 282-83.

Dean, David. “Much Ado? Possible Portrait of Shakespeare at the Art Gallery of Ontario.” History Today (Oct 2001) 51.10: 5.

DePalma, Anthony. “Behold That Special Face: Is It Shakespeare’s?” The New York Times 24 May 2001. nytimes.com. Web. 10 October 2015.

Foster, Kate. “Understanding the Doubling: A Meditation on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare.” Antigonish Review (Autumn 2003) 135: 99-103.

Gopnik, Adam. “Look here, upon this picture.” The New Yorker. 12 March 2009.

______. “The Poet’s Hand.” The New Yorker. 28 April 2014.

“New Image of Bard Revealed in Canada.” 2001. The Guardian, 25 May.

Nolen, Stephanie. “Expect Bard Mania, National Gallery Says.” The Globe and Mail, 16 May 2001. A7.

______. “Is This the Face of Genius?” The Globe and Mail, 11 May 2001. A1, A5.

______. “It’s Time to Reveal Shakespeare to the World.” The Globe and Mail, 12 May 2001. F8.

______. “Portrait Piques World Interest.” The Globe and Mail, 12 May 2001., A1, A7.

______. “Seeking John Sanders.” The Globe and Mail, 10 July 2001. R1, R3.

______. “Was This Male Face Shakespeare’s Love?” The Globe and Mail, 7 May 2002. A13.

Stoffman, Judy. “Bard’s Image Likely to Stay in Canada.” The Toronto Star, 12 May 2001. A26.

Film

Battle of Wills. Anne Henderson. InformAction, 2008. DVD.

Web-based Materials

Adams, James. “Reputed Shakespeare portrait prepares to strut upon the world stage.” The Globe and Mail. Globe and Mail Inc, 5 November 2013. Web.

Bona Hunt, Lori. “Lloyd Sullivan tells a family tale of history and controversy.” The Portico. University of Guelph, 2007. Web.

“Conference Explores Origins of Shakespeare Portrait.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, 16 January 2014. Web.

“December 2, 2013.” From the Second Storey. CFRU, Guelph. 2 December 2013. Radio.

“December 16 2013 – Pt 3.” As It Happens. CBC Radio. 16 December 2013. Radio.

Doucet, Jean-Pierre. “A Comparative Examination of the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare and the Droeshout Engraving of Shakespeare.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, 16 October 2015. Web.

“Experts Debate, Discuss Canadian Portrait of Shakespeare.” University of Guelph. University of Guelph, 28 November 2013. Web.

“Family Ties Strengthen Authenticity of Shakespeare Portrait.” University of Guelph. University of Guelph, 17 March 2011. Web.

Finn, Christine. “Will he be the One? A retired Canadian has spent his life savings on proving he owns a true picture of the Bard.” Sunday Times [London, England] 22 March 2009: 12. Web.

Fischlin, Daniel. “The Sanders Portrait.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. University of Guelph. 2004. 16 October 2015. Web.

Kahan, Jeffrey. “Is the Sanders portrait genuine?” Shakespeare Newsletter 51.4 (Winter 2001): 81+. Web.

“Sanders Portrait.” Wikipedia. < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanders_portrait>16 October 2015. Web.

“Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: Provenance and Genealogy.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, 27 February 2011. Web.

“Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: Reception History.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, 28 January 2011. Web.

“Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare: Science and Documentation.” Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project. Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, 10 May 2011. Web.

“Shakespeare sees and understands us.” The Portico. University of Guelph, 2007. Web.

“The Sanders Portrait.” Wartime Shakespeare in a Global Context. University of Ottawa, 2009. Web.

Vowles, Andrew. “Tracing the tests.” The Portico. University of Guelph, 2007. Web.

Newspapers (only)

Adams, James. “Art Painting Controversy: Face-off over Bare a battle of Wills.” The Globe and Mail 13 April 2009: R1. Print.

______. “Book titled Shakespeare’s Face fills void, portrait’s owner says.” The Globe and Mail 22 June 2002: A6. Print.

______. “Portrait passes ink test.” The Globe and Mail. 18 October 2007: R1. Print.

______. “Shakespeare’s Descendant: Ottawa portrait owner is the Bard’s kin.” The Globe and Mail 11 April 2009: R9. Print.

______. “The Great Shakespeare Faceoff.” The Globe and Mail 4 February 2006: R1 & R9. Print.

______. “Weekend Diary: Our Artsy Films! Our Shakespeare Portrait! Janet!” The Globe and Mail 25 September 2004: R3. Print.

Aspinall, Stacey. “Canadian man said to own only portrait of Shakespeare.” The Ontarion 5 December 2013: 4. Print.

Brown, Dineen L. “The Bard, or Bogus?; A 1603 Painting in Toronto Purports to Show the Young William Shakespeare.” The Washington Post. 25 July 2001. Print.

Dawson, Anthony B. “Entertaining Doubts.” The Globe and Mail 16 May 2001: A14. Print.

Gopnik, Adam. “Look here, upon this picture.” The New Yorker. Condé Nast, 12 March 2009. Web.

______. “The Poet’s Hand.” The New Yorker. Condé Nast, 28 April 2014. Web.

Nolen, Stephanie. “Face-off over a portrait.” The Globe and Mail 20 November 2002: R5. Print.

______. “Rare Shakespeare portrait will be exhibited at AGO.” The Globe and Mail 11 June 2001: A4. Print.

______. “What manner of man is this.” The Globe and Mail 22 June 2002: F1. Print.

______. “Stratford Festival will use the Bard’s portrait.” The Globe and Mail 26 September 2001: A17. Print.

______. “The picture speaks: After 400 years, says owner ‘It’s time to reveal Shakespeare to the world’.” The Globe and Mail 12 May 2001:F1 & F9. Print.

O’Flanagan, Rob. “Authenticity claim grows for Bard portrait.” Guelph Mercury. Metroland Media Group Ltd, 18 March 2011. Web.

______. “Shakespeare portrait sale has major U of G connection.” Guelph Mercury. Metroland Media Group Ltd, 16 December 2013. Web.

“Shakespeare Portrait.” Western Morning News and Mercury. Saturday 20 October 1928: 7. Print.

** “Suffolk and Norfolk Institutes of Archaeology: Meeting at Beccles.” The Ipswich Journal, and Suffolk , Norfolk, Essex, and Cambridgeshire Advertiser. Saturday 4 October 1862: 8. Print.

Van Gelder, Lawrence. “Test Favors Shakespeare Portrait.” The New York Times. 19 October 2007. Print.

Vowles, Andrew. “Faces of our ancestors a reflection of ourselves.” Guelph Mercury. Metroland Media Group Ltd, 5 December 2013. Web.

________

* The Sanders Portrait is also featured as a cover image along with a note regarding the scholarship on its provenance/genealogy and the forensic science done on it in the Shakespeare Made in Canada series published by Oxford University Press / Rock’s Mills Press. There are currently thousands of these books in circulation.

** This is the earliest know public reference to the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare. The Ipswich Journal reports that: “In the room was a presumed original portrait of Shakespeare. It had been in the family of the gentleman who exhibited it for nearly a century, and had always been considered to be an original portrait of Shakespeare.”

And …

“Perhaps the most noticeable thing in the room was a presumed original portrait of Shakespeare (1603), exhibited by Mr. S. H. Saunderson [sic; and presumably T.H. Sanders, Thomas Hale-Sanders, Lloyd Sullivan’s great-grandfather]. Of course, it is exceedingly doubtful whether this is a genuine portrait, for everything is doubtful about Shakespeare except his unexampled genius, but there is something suggestive of the character of the man in the appearance of the eyes in this portrait.”

Thomas Hale-Sanders’s (THS) father was Thomas Sanders who was christened Feb, 16, 1790 and died July 6, 1862. This exhibition took place in October 1862, so shortly after Thomas Hale-Sanders inherited the portrait from his father. THS may well have been trying to promote the recently inherited portrait, possibly with some hope of selling it. The name of the owner is given in The Ipswich Journal report as S. H. Saunderson, which would not be the first (or last) instance of a reporter misreporting a name.

The description of the portrait, especially the mention of the eyes and the fact that it is dated 1603, is wholly consistent with the Sanders portrait and the report uses similar language to the M.H.A. Spielmann essay, written almost half a century later. That essay states: “It had been in the family of the gentleman who exhibited it for nearly a century, and had always been considered to be an original portrait of Shakespeare.” Spielmann, a well-known Victorian art critic and editor, quotes Thomas Hale-Sanders as saying “that the portrait had been for nearly a century in the possession of his relations, and had always been supposed to be a portrait of Shakespeare.”

Jace Weaver at Guelph: “Shakespeare Among the Salvages” / Introduced by Thomas King

The School of English and Theatre Studies, the Department of History, and the College of Arts will host Jace Weaver’s public talk, “Shakespeare Among the Salvages” on Thursday, November 12th at 4:00 p.m. in Massey Hall, Room 100 (Lower Massey). He will be introduced by Thomas King. All are invited.

Jace Weaver (Cherokee) is Director of the Institute of Native American Studies, Franklin Professor of Native American Studies and Religion, and Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Georgia. He holds two doctorates, a J.D. from Columbia Law School of Columbia University and a Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in New York.

Dr. Weaver’s work in Native American Studies is highly interdisciplinary, though focusing primarily on three areas: religious traditions, literature, and law. He is the author or editor of a dozen books, including That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community, Other Words: American Indian Literature, Law, and Culture, Turtle Goes to War: Of Military Commissions, the Constitution and American Indian Memory, and Notes from a Miner’s Canary: Essays on the State of Native America.

In 2003, Dr. Weaver won the Wordcraft Award for Best Creative Non-Fiction from the Wordcraft Circle of Native American Writers for Other Words. In 1999, he won the Portfolio Award for excellence in teaching resources from the journal Media and Methods for his book on CD-ROM, American Journey: The Native American Experience. He has also been nominated for the Oklahoma and Connecticut Book Awards. American Indian Literary Nationalism, written with Robert Warrior, Craig Womack, and Simon Ortiz, won the 2007 Bea Medicine Award for best book in American Indian Studies from the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies and the Native American Literature Symposium.

In Other Words, Dr. Weaver has written, “Native American Studies is by its nature two things, comparative and interdisciplinary.” His most recent work, published in 2014, is The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000-1927. The Red Atlantic, Jace Weaver’s sweeping and highly readable survey of history and literature, synthesizes scholarship to place indigenous people of the Americas at the center of our understanding of the Atlantic world. Weaver illuminates their willing and unwilling travels through the region, revealing how they changed the course of world history.

Indigenous Americans, Weaver shows, crossed the Atlantic as royal dignitaries, diplomats, slaves, laborers, soldiers, performers, and tourists. And they carried resources and knowledge that shaped world civilization–from chocolate, tobacco, and potatoes to terrace farming and suspension bridges. Weaver makes clear that indigenous travelers were cosmopolitan agents of international change whose engagement with other societies gave them the tools to advocate for their own sovereignty even as it was challenged by colonialism.

Reviews of The Red Atlantic

“In this fascinating, well-written account that places Native people at the center of Atlantic world history, Weaver positions the Atlantic as a conduit not only for the physical movement of people and ideas, but also as a highway for connections between cultures. . . . Highly recommended.”

–Choice

“The Red Atlantic is an original, learned, and comparative historical narrative of transatlantic cultures and nations. Jace Weaver considers the significance of the cultural exchange, political ideas, literature, technology, and material trade with Native American Indians, or the historical and cultural transatlantic significance of the Red Atlantic. He has written an extraordinary and comprehensive comparative history of Native American Indians in the Red Atlantic, and his discussions of the subject will surely inspire and influence future students, research, and writing on the subject.”

–Gerald Vizenor, University of California, Berkeley

“Following in the wake of Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic, this book re-visions the Atlantic as Native space. Indians inhabited an Atlantic world and participated in the multiple lanes of exchange that developed following Columbus’s voyages. Native foods, technologies, and ideas traveled to Europe; Native people traveled to Europe (sometimes more than once) as captives and slaves, as soldiers and sailors, as diplomats, and occasionally as celebrities. And writers, both Native and non-Native, created a fictional literature of the Red Atlantic. An important and stimulating book.”

–Colin G. Calloway, Dartmouth College

Shakespeare Made in Canada Series at Rock’s Mills Press

Rock’s Mills Press, founded by former CEO of Oxford University Press David Stover, has recently contracted the Shakespeare Made in Canada Series as part of its mandate to publish “books that matter” For more on the series please click here.

The Shakespeare Made in Canada Series is edited by Daniel Fischlin and features:

-

New playtexts and annotation draw on the best international research

-

Scene summaries, character synopses, notes on the text, and tips for reading Shakespeare provide points of entry into complex early modern plays

-

Introductions by leading academics; prefaces by diverse Canadian voices including Paul Gross, Martha Burns, Sky Gilbert, and Daniel David Moses

-

Engaging, peer-reviewed Shakespeare editions for Canadians new to the plays

The Series Advisory Board consists of distinguished Canadian Shakespeareans Donald Beecher, Carleton University; Susan Bennett, University of Calgary; Mark Fortier, University of Guelph; Janelle Jenstad, University of Victoria; Susan Knutson, Université Sainte-Anne; Jill L. Levenson, University of Toronto; and Irena Makaryk, University of Ottawa.

All of the books published in the series feature the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare on the cover and include a short note on the portrait’s genealogy/provenance, the science surrounding the portrait, and the internal evidence associated with the portrait.

A Comparative Examination of the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare and the Droeshout Engraving of Shakespeare

A Comparative Examination of the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare and the Droeshout Engraving of Shakespeare: A Software Approach to the Mystery of Shakespeare’s Face

Jean-Pierre Doucet and Maude Doucet

In 2009 Andreas Kahnert used Photoshop to compare the Droeshout engraving and the Cobbe portrait (1). Significantly, his results have contributed to a definitive ruling out of the Cobbe as an authentic portrait of William Shakespeare. After watching Anne Henderson’s documentary Battle of Wills (2) about the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare, the only known portrait painted during his lifetime, we became fascinated with the various controversies regarding that claim and decided to explore further the comparison of the Sanders Portrait and the Martin Droeshout engraving mentioned in that documentary.

In what follows, a direct facial comparison approach is done using visual imaging software to compare the Sanders portrait with Droeshout’s famous engraving of Shakespeare (used as the frontispiece on the title page to the 1623 First Folio), and generally regarded as an ill-achieved yet somewhat accurate representation of Shakespeare late in his life by a young engraver (22 years old) yet to achieve the technical mastery he was to display later in his career. This comparative approach is possible because of a specific feature common to each artwork derived from the fact that the subjects in both works are shown from the same perspective. Further, as a complement to the present study, the Chandos portrait was also studied using similar techniques. This paper summarizes some of the findings based on the unique comparative analysis the software permits.

Being aware of the likely critics of the approach chosen (software that permits sophisticated analysis of facial features), a tool to do the work automatically, in order to minimize any user involvement, was needed. The FACE-OFF facial recognition software used for the current study fulfills that requirement. Developed by Bob Schmitt (from visualfacerecognition.com), the concept behind the software is deceptively simple as Mr. Schmitt describes it (and we summarize):

- by finding the center of the eyes on both images with the help of a magnifier that one can move with a mouse, the software is able to normalize images;

- the software also rotates the faces as best as possible and the eyes are put on the same horizontal plane;

- then the pictures are placed so that a direct comparison can be done by sliding each image over each other as the user sees fit;

- and a full superimposition of the pictures can also be done with the software allowing for close comparison.

The main basis of this software is to adjust each picture to the same interpupillary distance (IPD). In adulthood the IPD is a constant value (3) and this anatomical reference marker is used regularly for forensic facial identification (4, 5).

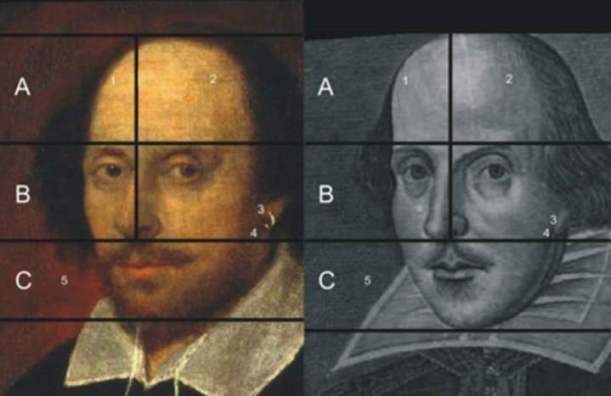

Although similar results were obtained with the final state of Droeshout engraving (data not shown), the first state of the Droeshout engraving (6) was used in parallel to the Sanders portrait (7) for this comparison. From the start it was apparent that the comparison at the level of the mouth would not be that good given the very different “looks” of the sitter––in the Sanders portrait the subject is faintly (if intensely and enigmatically) smiling while in the Droeshout engraving Shakespeare is deadly serious with no smile at all.

Regardless of this difference, the FACE-OFF software was used to identify the center of each eye in each picture. Then the software did the rest automatically. Some of the screen-captures (using Corel Painter Essentials3 software) of the results are shown in the Fig. 1. The top screen-capture shows both subjects side-by-side, having the same IPD and their eyes put at the same horizontal level. And as the software cursor moves, the subject of the Sanders portrait fades in while Shakespeare’s face in the Droeshout engraving fades out. These screen-captures demonstrate how the Sanders portrait and the Droeshout engraving are closely related to each other.

Fig. 1: Various screen captures of the FACE-OFF comparison between the first state Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare and the Sanders portrait.

Though a detailed Table including various comparative measurements could have been made, we wanted to keep things simple for this essay by adding to the first FACE-OFF screen-capture parallel lines that already put in evidence the major facial features similarities observed in the screen-captures and by numbering the most obvious similarities found from all the screen-capture pictures (Fig. 2). These include: the same size of forehead (Fig. 2 panel A); the same size of the eyes and nose areas (Fig. 2 panel B); the same height of the lower facial anatomy (Fig. 2 panel C); the same height between the eyebrows and the chin (Fig. 2 panels B + C); the same total facial height (Fig. 2 panels A + B + C) in each image.

Among the main similarities, it is possible to find: 1) a similar baldness pattern; 2) same large forehead; 3) similar delicate eyebrows; 4) similar space between the eyebrows; 5) same hairstyle; 6) similar eyelids and dark rings under and above the eyes; 7) similar right facial contour line up to the right eyebrow; 8) similar nose shape and nostrils; 9) very similar left ear lobe (attached and itself a fairly rare anatomical marker); 10) similar thin moustache above the upper lip; 11) similar thin upper lip; 12) similar chin; 13) and a similar left jaw line.

The extent of these detailed similarities is an exceptional indicator of contiguity between the images.

Fig. 2: The similarities observed from the screen-captures obtained with the FACE-OFF software when comparing the Droeshout engraving and the Sanders portrait. Parallel lines were first drawn to highlight the main facial similarities, forehead (panel A), eyes and nose areas (panel B) and bottom part of the face (panel C) in each image. The more specific similarities were numbered and described in the text.

After all these similarities were found using this direct comparison methodology, the question remains: can we say that the two subjects are the same? As Schmitt writes in his software description, there is no way to be 100% sure that two people are the same.

Nonetheless in light of the remarkable comparative correspondences revealed by the software analysis, how is it possible to see so many similarities between two different artworks done by two different artists using two different media (painting and engraving) and done nearly two decades apart (1603 and 1622)?

It appears obvious, too, that following the present comparison, the Droeshout engraving was a work carefully done from a very precise model, perhaps even a pre-existing portrait like the 1603 Sanders portrait. As mentioned previously, the FACE-OFF software also gives the user the possibility to do an overlay of the pictures compared. The first time we saw this overlay shown in Fig. 3––the left ear lobe superposition, the right eyebrow continuation, the remarkable correlation of facial outlines and shapes, and so forth, we were speechless, so close were the features.

Add to this the fact that both images have the relatively rare anatomical feature of the (left) attached earlobe in plain display and it becomes very possible that the Sanders portrait was in fact the source image for the Droeshout engraving. And one can still see the faint smile of the Sanders portrait subject as a subtle aspect of the Droeshout engraving.

Fig. 3: Overlay of the Droeshout engraving and the Sanders portrait using the FACE-OFF software.

To test these results, obtained with specific facial recognition software, another tool was chosen, CorelDRAW X3 Graphics Suite. This software has plenty of useful features, including an eraser that was used to remove the smile from the Sanders portrait. After importing the Sanders portrait, erasing the mouth of the subject, importing the Droeshout engraving, measuring the IPDs, re-sizing the pictures accordingly (using the ratio of the IPDs measured), slightly rotating (1 to 2 degrees) and making transparent the Droeshout engraving, it was then possible to superpose both images as seen in Fig. 4. Many convincing screen captures were also obtained using the CorelDRAW software while sliding the Droeshout engraving over the Sanders portrait (data not shown but available if needed). The different software chosen to compare the Sanders portrait and the Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare give highly similar if not identical results (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 4: Superposition of the Droeshout engraving over the Sanders portrait after having erased the smile in the Sanders portrait using CorelDRAW software. Note the more formal representation of the ruff in the Droeshout as opposed to the friendship mode in which the Sanders Portrait is painted.

Since the angle of the subject was also good, the FACE-OFF software was then used to compare the Chandos portrait (8) with the first state Droeshout engraving (6). As stated earlier, after having marked the center of the pupils in each picture, the FACE-OFF software did the rest. Automatically the software resized the pictures to the same IPD and without any involvement from the user it rotated if necessary the pictures and put the eyes on the same horizontal plane. Some of the screen captures obtained by using this procedure are shown in Figs. 5 (a,b,c).

Figs. 5 (a,b,c): Various screen captures of the FACE-OFF comparison between the Chandos portrait and the first state Droeshout engraving.

For this comparison it is easier to describe the major differences than the similarities. Indeed many major differences between the Chandos portrait and the Droeshout engraving were observed in those screen captures and are summarized in Fig. 6. Again, as was done for the Sanders portrait/Droeshout engraving comparison, parallel lines were added to the first screen capture of the Fig. 5 (A top, B middle and C bottom parts of each face). Furthermore, since both subjects were very serious (very similar closed mouths), a perpendicular line was also added in each picture just above the point where the nasal septum meets the upper lip.

The major differences for the Chandos portrait compared to the engraving were numbered as followed: 1) distinct right forehead; 2) distinct left forehead 3) wider left ear lobe tip; 4) wider space between the bottom of the nose and the left ear lobe tip; and (5) a shorter height of the C panel, that is, the space between the bottom of the nose and the chin.

It is important to remember that Shakespeare’s close friends recognized the Droeshout engraving as an acceptable representation of the Bard. The present study has shown many similarities and correlations between the Sanders portrait and this famous engraving. At the opposite end of the spectrum, major facial differences are observable when the Chandos portrait is compared to the engraving. The Chandos portrait does not appear to be related to the Droeshout engraving in any significant way.

Fig. 6: The major differences observed from the screen-captures obtained with the FACE-OFF software when comparing the Chandos portrait and the Droeshout engraving. Parallel lines were first drawn to highlight the forehead (panel A), eyes and nose areas (panel B) and bottom part of the face (panel C) in each image. A perpendicular line just above the point where the nasal septum meets the upper lip was also added in each picture. The major differences are numbered and described in the text.

To conclude, the image of Fig. 4 may well represent the way the Bard looked during the last period of his life, while the Sanders portrait may show him at an earlier time. It is clearly possible, based on the exceptional number of similarities between the Sanders and the Droeshout, that Droeshout used the Sanders portrait as the model for his engraving.

References:

1. http://www.uni-mainz.de/eng/13084.php; a study by H. Hammmerschmidt-Hummel. The Cobbe portrait is not a genuine likeness of William Shakespeare made from life as confirmed by four experts. Further, the eminent early modern portraiture expert Sir Roy Strong has publicly called the claims about the Cobbe, “codswallop” (http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2009/apr/19/shakespeare-portrait-contested).

2. Anne Henderson, Battle of Wills. Film produced by InformAction, Québec, Canada, 2008, HD colour (52 minutes).

3. T. Filipovic, Coll. Antropol. 27 (2003) 2: 723-727.

4. F.C. Loh, T.C. Chao, J. Forensic Sci. 34 (1989): 708-713.

5. G. Porter, G. Doran, Forensic Sci. International 114 (2000): 97-105.

6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Droeshout_first_state.jpg.

7. http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca/multimedia/imagegallery/sanders_large.jpg.

8. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Shakespeare.jpg.

Acknowledgments: We thank Lloyd Sullivan and Daniel Fischlin who generously gave us access to the information needed to complete this work. Dr. Fischlin was also very patient in helping edit this paper. We also thank Bob Schmitt for making such superlative software.

The Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare in The Poet’s Hand by Adam Gopnik (The New Yorker)

Yet another take on the Sanders Portrait of Shakespeare from Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker.

You must be logged in to post a comment.